Elements of a Comprehensive Heat Stress Program – Quick Tips

Introduction

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illness Data in 2018 there were 3,120 heat exposure cases that resulted in days away from work. The BLS Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries showed exposure to environmental heat was the primary or secondary cause of 49 deaths in 2018. With better planning and awareness training regarding the signs and symptoms of heat induced illnesses, many of those cases could have been avoided.

Regulations

The Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) addresses working in hot environments in general industry under a variety of standards:

- OSH Act General Duty Clause 5(a)(1)

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) assessment 29 CFR 1910.132(d)(1)

- Provide potable water 29 CFR 1910.141

State-level OSHA plans that address heat stress in the workplace:

The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has established Criteria for a Recommended Standard addressing Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments.

Any worker exposed to hot and humid conditions, either outdoors (construction, landscaping and surface mining) or indoors in hot environments (bakeries, boiler rooms and foundries, etc.) are at risk of heat stress. Putting a plan into effect when the heat index temperature is above 80° F and adjusting the workload based on current and anticipated conditions are key components of any comprehensive heat stress program.

Heat Stress Prevention Plan

Here are seven key elements to an effective heat stress prevention plan:

- Written policy

- Hierarchy of controls

- Heat acclimatization plan

- Environmental monitoring

- Training

- Hydration

Written Heat Stress Policy

Being proactive by having an established heat stress prevention policy in place before the heat index level rises is critical. Elements of a written heat stress policy include:

- Purpose / Scope

- Responsibilities

- Supervisors

- Employees

- Safe work procedures

- Heat acclimatization plan

- Hydration

- Medical monitoring

- Environmental monitoring

- Training

- Signs and symptoms

- Emergency procedures

- Program evaluation

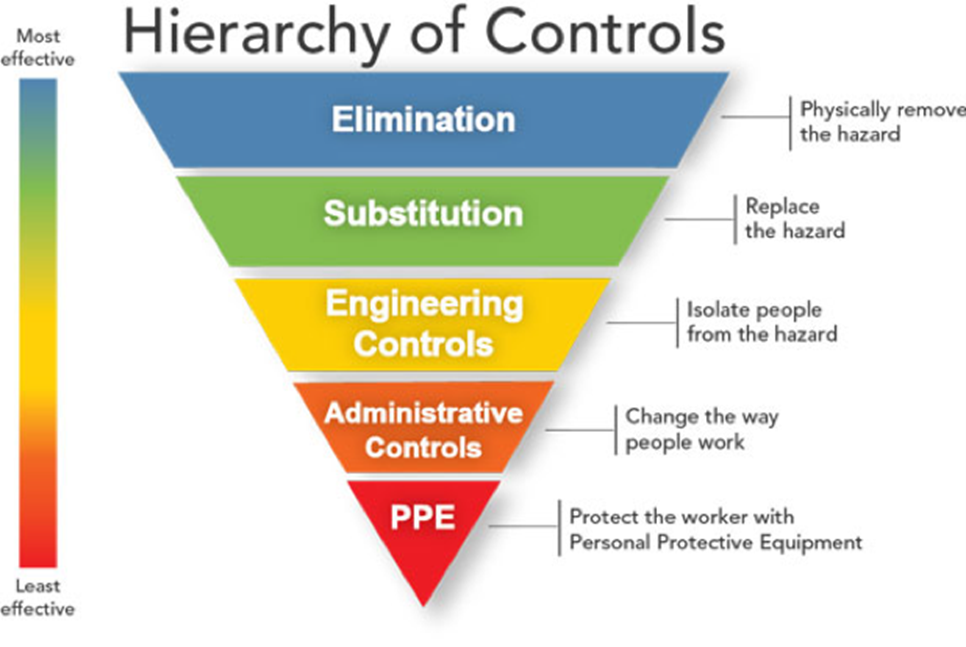

Hierarchy of Controls

NIOSH’s Hierarchy of controls is a way of thinking about and applying specific actions to reduce or eliminate potential exposures to identified hazards. This is a commonly used and understood practice within the safety community. In this philosophy, you always apply the most effective method first, working down from there.

Engineering Controls

If eliminating the hazard or substituting are not feasible then engineering controls are used. Engineering controls are changes to equipment or to the work process that isolate people from the hazards. They do not depend on people to provide protection. The best way to prevent heat-related illness is to make the work environment cooler. There are a variety of engineering controls that address the actual source of heat and eliminate the workers heat exposure. Some examples of engineering controls that can be used to reduce employee exposure to heat include:

- Air conditioning

- Increase general ventilation

- Cooling fans

- Local exhaust ventilation

- Insulation of hot surfaces

Administrative Controls

OSHA considers administrative controls as measures aimed at reducing employee exposure to hazards. If it is not possible or practical to eliminate sources of high heat, employers can establish work policies and procedures to reduce the length of time workers are exposed to heat hazards. Some examples of administrative controls for workers exposed to a high heat environment include:

- Having workers who have strenuous jobs rotate in and out of the hot environment to reduce exposure

- Adjusting the work schedule, having strenuous work done during cooler parts of the day such as early morning or evenings, or possibly rescheduling activities for a cooler forecasted day if feasible

- Adjusting the work/rest schedule to include more frequent breaks allowing employees to leave the hot environment

- Having additional workers to reduce the physical demands during hot weather

- Providing heat stress training for all workers who are exposed to high heat

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is always the last control to consider. PPE provides a barrier between the worker and the heat source. Examples of heat stress protective PPE include cooling hats, sweatbands and hardhat cooling products like neck shades, bandanas, sun shields, vests and cooling pad inserts. There are three basic kinds of cooling vests:

- Liquid cooled vests – circulates cooled liquid

- Evaporate garments – soaked in cold water and relies on evaporation for cooling

- Passive change style vests – equipped with ice packs

Heat Acclimatization Plan

Employers should develop a heat acclimatization program. This program typically falls into two groups of workers: new workers or workers with previous experience. These workers need a period of time to get accustomed to the heat. According to NIOSH to accomplish acclimatization:

- Gradually increase workers’ time in hot conditions over seven to 14 days.

- For new workers:

- The schedule should be no more than 20% of the usual duration of work in the heat on the first day and no more than 20% increase on each additional day.

- For workers with previous experience:

- The schedule should be no more than 50% of the usual duration of work in the heat on day one, 60% on day two, 80% on day three, and 100% on day four.

- Closely supervise new employees for the first 14 days or until they are fully acclimatized.

- Recognize that non-physically fit workers require more time to fully acclimatize.

- Acclimatization can be maintained for a few days of non-heat exposure.

- Taking breaks in air conditioning will not affect acclimatization.

The lack of acclimatization has been shown to be a major factor associated with worker heat-related illness and death.

Medical Monitoring

It’s important for employers to institute a medical monitoring program for employees who work in hot environments. The program should include components of medical screening and surveillance with the goal of early detection of heat-related illnesses.

Suggested components of a comprehensive medical monitoring program should include employee training, preplacement medical examinations, periodic follow-up evaluations and heat-related illness incident reporting.

Environmental Monitoring

It’s important to track weather daily at work sites when forecasts are predicting daytime highs to reach 80°F or higher. Both the heat index and wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) are used to evaluate environmental temperature in hot environments. WBGT is calculated by measuring dry air temperature, humidity and radiant energy which is used to determine a thermal load on the employee. Because of certain limitations, many small businesses may not have the means to determine WBGT.

Training

Training for heat stress prevention will help reduce the risk of heat-related injury and illness before it becomes an issue. Having a comprehensive heat illness training and prevention program that highlights the symptoms of overexposure to heat stress is important for any employee at risk to experiencing heat stress in the workplace.

All affected employees need to be trained on:

- Recognition of the signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses and administration of first aid.

- Causes of heat-related illnesses and the procedures that will minimize the risk, such as drinking enough water and monitoring the color and amount of urine output.

- Proper care and use of heat-protective clothing and equipment and the added heat load caused by exertion, clothing, and personal protective equipment.

- Effects of non-occupational factors (drugs, alcohol, obesity, etc.) on tolerance to occupational heat stress.

- The importance of acclimatization.

- The importance of immediately reporting to the supervisor any symptoms or signs of heat-related illness in themselves or in coworkers.

- Procedures for responding to symptoms of possible heat-related illness and for contacting emergency medical services.

Hydration

The key to keeping workers safe in hot environments is staying fully hydrated, because a dehydrated person is more susceptible to show symptoms of heat illness. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends that employers provide the means for hydration and encourage their workers to hydrate themselves with cool potable water (between 50 and 60°F) made accessible near the work area. To maintain proper hydration it is important not to wait until becoming thirsty to drink fluids.

During short-term (<2 hours) of moderate physical exertion, 8-ounces of water every 15-20 minutes is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to stay properly hydrated. The CDC advises the use of sports drinks containing balanced electrolytes during periods of prolonged sweating lasting several hours or more. In these periods of more intense exertion, sports drinks can replenish and rebalance electrolytes levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are some additional risk factors that can lead to heat stress?

A: According to the CDC, workers who are at increased risk of succumbing to heat stress include those who are 65 years or older, overweight, have heart disease or high blood pressure, or take certain medications that have side effects that are triggered by extreme heat.

Q: What is the recommended sun protection factor (SPF) for sun screen for outdoor workers?

A: OSHA suggests sunscreen with at least a 30 SPF or greater. Liberal amounts should be applied 30 minutes before exposure and then every two hours throughout the day.

Sources

OSHA Safety and Health Topics: Heat

NIOSH’s Criteria for a Recommended Standard Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments

CDC’s Extreme Heat Resource Center

The information contained in this article is intended for general information purposes only and is based on information available as of the initial date of publication. No representation is made that the information or references are complete or remain current. This article is not a substitute for review of current applicable government regulations, industry standards, or other standards specific to your business and/or activities and should not be construed as legal advice or opinion. Readers with specific questions should refer to the applicable standards or consult with an attorney.

Source: Grainger Know How – https://www.grainger.com/know-how